At The Kite Factory, we are huge fans of JIC (Joint Industry Currencies) media research. They deliver gold standard, independent, and properly governed data on who read/watched/streamed a particular media event and was therefore exposed to the investment we made on behalf of our clients. They allow us to establish causal relationships with our clients’ commercial outcomes and enable us to continually optimise the effectiveness of their investments.

The pandemic has severely impacted the delivery of JIC data, particularly from channels that deliver non-continuous measurement. RAJAR, who measure radio listening via a quarterly survey, were no exception to this, and consequently have suspended measurement and reporting over the last year. Back in summer 2020, we advised clients to be cautious when investing in radio and to consider that consumer habits will have changed, as we have seen across all media. We then awaited RAJAR to resume research and publication.

As an independent media agency, we’re able to invest budget in channels where we believe that the client will see the best return. To ensure we’re able to make the best-informed decisions we rely on industry data to understand where our audiences are, what media they consume and how they do so. In the absence of this, these decisions would be pure guesswork, which is why we were excited to see new research published last week by Radiocentre, the body that exists to “promote strong, successful and brilliant commercial radio”. Mindful of this mission statement but starved of radio listenership data for the past year, we eagerly read it.

The report (published on 2nd March) entitled “New ways of working; New ways of connecting” talks of the white collar, affluent and higher educated WFH audience. Readers will know that we also see this as a valuable audience; one likely to persist for the foreseeable future; and one open to other changes in their lives. So, what claims did radio make as to the presence it has in this audiences’ lives?

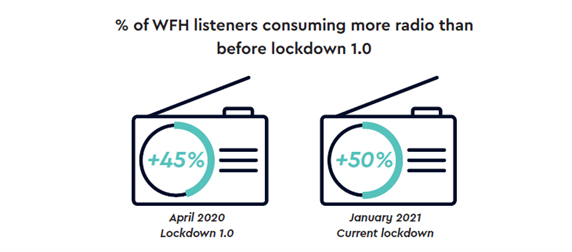

The first is that 56% of those of use working from home are commercial radio listeners. Testing this with the last RAJAR figure we have – 66% of adults listened to commercial radio at least once a quarter- this makes sense. However, the next finding surprised us. Figure one, below, asserts that WFH radio listeners are listening to more radio in 2021 than in 2020.

Figure One: The Radio centre claim that working from home radio listeners are listening to more radio in 2021

Source: New ways of working, new ways of listening report, Radiocentre 2021

Source: New ways of working, new ways of listening report, Radiocentre 2021

This surprised us because as a rough rule of thumb, around 50% of pre-pandemic radio listening was out of home: in the car, at work, or travelling. Since March last year, the WFH audience haven’t been commuting or at work and thus the opportunities to listen in their old habits no longer exist. Had all that listening merely switched to in home listening?

Radiocentre’s research had found that some radio listeners were listening to more radio now than they were before. In other words, dwell time and frequency have increased for some. But what about the overall numbers of people listening to radio, in other words reach?

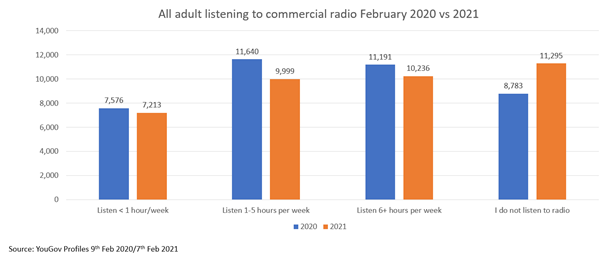

In the absence of RAJAR we turned to YouGov, on the basis it could give us comparable data for each year. YouGov methodology uses a rolling 52-week data set, so we have a fair representation of 2019 and 2020 in the numbers we are showing below. We chose a “normal” week (pre pandemic) of 9th February 2020, and the closest week in 2021, week of 7th February. Rather than growth in radio listening, we found a sharp contraction: figure two below shows a 5% decline in the number of radio listeners year on year.

Figure two: We found declining numbers of adults listening to radio February 2021 vs February 2020

Source: AA/WARC

Source: AA/WARC

Reach dropped in light, medium and heavy commercial radio listeners. 2.5 million fewer adults claimed to listen to any radio at all – that equates to a 5.5% decline in reach for commercial radio.

If true, the finding in figure two is highly significant. By these numbers, commercial radio reach is down to 52%, which means any normal campaign probably won’t reach the ears of more than 40% of the population. However, much of radio’s power as a medium comes from its ability to target different audiences based on their listening habits. We delved deeper to understand whether this fall in reach was driven by any particular audiences.

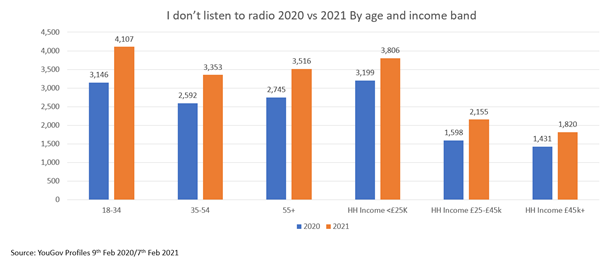

Figure three shows that audiences appear to have been lost across all age and income bands. The largest losses are in the under 34’s, once the loyal heartland of commercial radio.

Figure three: Radio appears to have lost audiences across all age and income bands

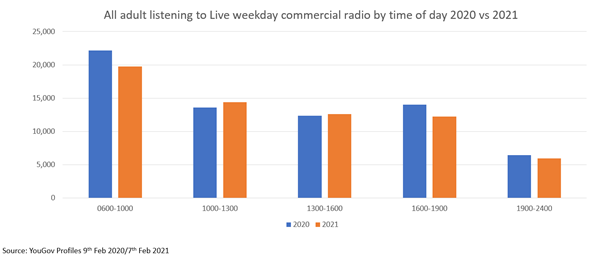

Fortunately for radio, the young (for reasons covered in past mailers) may not be the most highly demanded audience for advertisers in 2021. We wondered if there were any other risks to revenue. For example, to the premium, high reach, drive time times of day that traditionally delivered a high reach of audiences when they were unavailable to other media channels. Unfortunately for radio, we found that’s where the damage was most severe, as figure four below shows.

Figure Four: The largest audience falls are in drive time dayparts – the traditional heartland of radio

Listening actually increased during the 1000-1300 timeslot, which we attributed to us all getting up later and the WFH impact as researched by Radiocentre.

We then wondered once again if we were being unfair. Figure four shows listening for all live radio on weekdays. We also checked listening on weekends and found no evidence of a shift towards weekend listening.

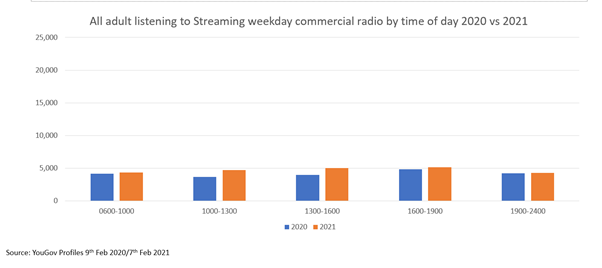

In a world where media is rapidly shifting to online and on-demand, had listening also moved from live to streaming services? Figure five gives us the answer. Note that the axis is on the same scale as for figure four, which is why the numbers seem so small.

Figure five: Streaming services have gained listeners, but a fraction of those lost to live broadcast

Streaming services have gained listeners in every time band across the day, with the largest gains made in the daytime, whilst our WFH audience could be working and available. However, the numbers are still small when compared to those lost to live broadcast.

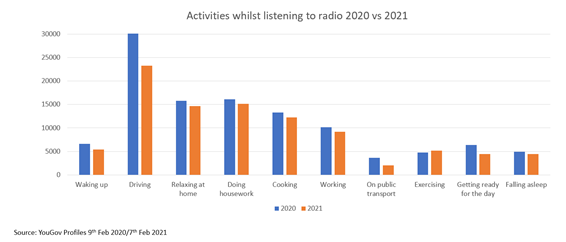

We applied one last cross-check to our data and asked not what time of day the losses came from, but rather what audiences were doing last year vs this year when they listened to radio. Could we correlate audience loss with changed behaviours in real life, as we have done for other media channels?

Figure six shows that we can and that the findings support the common sense arguments as to why radio will have lost audiences.

Figure six: Radio listening was correlated with behaviours that are diminished in our new world

The biggest falls in audiences are seen at the times when we were driving, on public transport, or waking up. The falls are not because we don’t listen to radio when we do these things, but because in the case of driving and public transport, we don’t do them anymore. Our wake-up times have shifted back by up to an hour as fewer of us commute. That changed habit has meant a change in listening habit and we suspect this is the heart of the problem. Radio listening, more than any other media consumption, was habitual. Listeners listened to the same (small) repertoire of stations, at the same time, every day. Break one part of that habitual loop (e.g., travel to work) and all the associated habits fall apart.

The implications of this, with many commuters not returning to the office full time, could have as big an impact on radio as on OOH and transport media. Maybe more so as radio has lost reach whereas OOH has merely lost frequency – people are still going out, just less often and to different places. Whilst engaged listeners may be increasing their time spent with audio, changes to daily routines over the longer term may mean lost listeners from radio’s traditional heartland.

So, what does this mean for advertisers and should we all abandon radio and cease any investment in it? The short answer is no. If you are a smaller advertiser who only uses radio in conjunction with search and social media, then you almost certainly won’t notice any difference. The biggest impact will be felt by larger advertisers who are using radio in conjunction with TV to add frequency and extend the uplift effects that broadcast media have on digital response harvesting channels.

Radio will still add frequency to a TV schedule, but not in the same effective way as in 2019. The cross-media reach (e.g., those seeing TV and hearing the radio ad) will be lower. That’s because radio will reach fewer of those who see the TV commercial. If you continue to invest the same budgets and the same proportion in TV and radio, then those who hear the radio will hear it more frequently. And that might be annoying for some consumers.

So, what’s our advice if you are investing in radio?

Firstly, check the price you are paying. The CPM’s for radio are still being set using old RAJAR data. If we are right that data overclaims the number of listeners delivered, it may be that radio represented good value historically for your organisation that doesn’t matter. But for marginal investments, it will. Check and decide in the light of your own results.

Secondly, if you are using radio check that the strategic reason for using it is still valid. The changes to people’s listening habits described above may have affected your target audience. For example, it may be necessary to expand into new dayparts or new audio platforms to top up your reach.

This piece has focused heavily on media metrics, contending that radio may be trading some of its reach for frequency. This may seem detached from business outcomes, but business growth is driven by great leaps forward and attention to all the details. This seems to be one of those details that matters.