At some point, sustained increased investment in a certain tactic will become inefficient. But how do you ensure budget is being optimised?

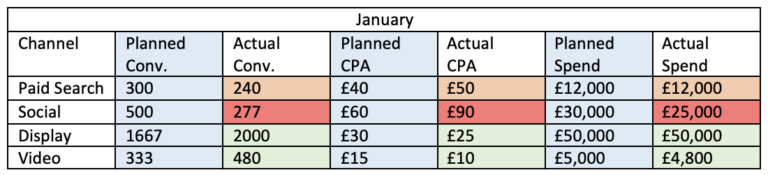

If you’re up to date with our January and February instalments and playing along at home, you’ll have a table to hand that looks a bit like this (conditional formatting optional, but our previous instalment explains all):

(For the purposes of demonstration, we will be assuming a last-click attribution model is in use)

As each month progresses, you’ll need to update the actual performance figures against your projections. It’s up to you whether you create a phasing table for each month, or whether you update the same table cumulatively, or pivot-table the whole thing.

I prefer keeping them separate so I can easily see the investments, insights, optimisations, and re-allocations for each month. This makes it easier to provide narrative to stakeholders as to what decisions have been made over the course of the quarter and why.

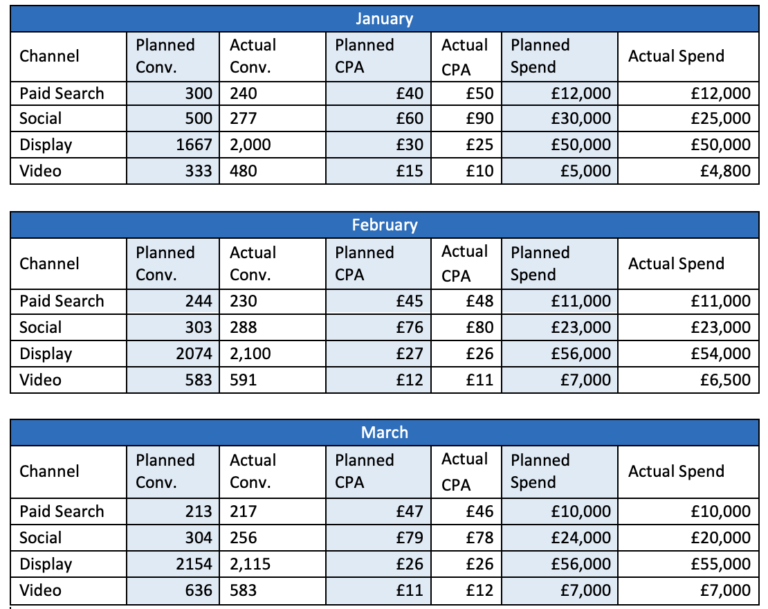

Here’s Q1 performance in phasing table form:

As you’ve been analysing your performance data, re-allocating budget, and re-assessing, you may have noticed that there is a point in your channel investment where suddenly your CPA jumps up. As an example, you can see from the phasing tables above, we’ve decreased our imagined paid search investment and the CPA has decreased.

Outside of channel optimisations, the decrease in efficiency that comes along with increased investment is known as ‘diminishing returns’.

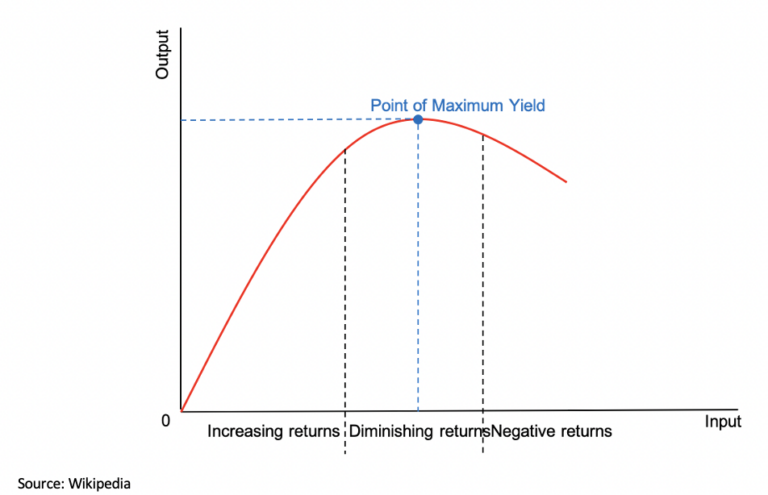

In the graph above, you can see the ‘point of maximum yield’ (POMY).

When you have reached this point, you will be receiving the best possible results (output) for your budget (input). Although the input and output have correlated up until this point (increasing returns), if we were to continue to increase the input (the budget) at a sustained rate, we’ll find the output (for example, your cost per conversion) becomes less efficient.

This decrease in efficiency is known as the point of ‘diminishing returns’.

It is at this stage where action must be taken; budget must be re-distributed either across channels or more efficiently within channels to realign performance with the POMY.

This doesn’t mean you need to spend less to be efficient; it just means you need to spend wisely. To successfully address the impact of diminishing returns, it’s important that we understand not only how our budget is being allocated, but how our spend is managed within the platforms we’re using.

For example:

You’re running a search campaign with a ‘Maximise Clicks’ bid strategy in an effort to drive as much traffic to your website as possible, logically leading to an increased volume of conversions. That’ll work… right?

In this instance, Google will be aiming to serve your ads to users who are most likely to click on your ad; whether or not they are deemed likely to purchase. This approach will likely provide you with lots of website visits, and a number of ‘base’ conversions, garnered from users who luckily seemed to be ready to convert whether Google knew it or not.

The approach used in this example causes a high degree of wasted budget on users who didn’t necessarily have any purchase intent. This wasted budget inflates CPAs artificially causing the point of diminishing returns to be hit prematurely.

By switching to a ‘Maximise conversions’ bid strategy, (as well as the potential to narrow targeting down to in-market audiences), budget spent on users without conversion intent should be minimised; this causes a decrease in CPA, staving off the point of diminishing returns.

As you might imagine, each platform differs in how diminishing returns impacts performance so I checked in with Gabby Krite, our head of digital operations to get her take on the impact we see in social.

She explained: “The maximise clicks example on Google also applies to social – most social conversions are post click so it seems logical to choose the traffic option to optimise towards to improve conversions. However, the algorithm then focusses on people most likely to click, not purchase.

“The focus should be on improving relevance of the ad against your target audience, whilst optimising towards conversions. You are improving traffic volumes, within the constraints of your most valuable people.”

A common struggle with social is finding the balance between a broad and specific audience:

Small audience – if this works in the first instance you will optimise aggressively towards it and over time you will see your CPA decrease as your audience either converts or goes message blind. Facebook will still spend the money and so your frequency will increase against unconverted users that have not been convinced yet.

Next steps – expand audience, try a new audience or change your message to address their barrier to conversion

Small audience – it isn’t uncommon for the algorithm to flag that it has insufficient data to optimise from (recommended 50 conversions per ad set per week). It’s very difficult to get out of this situation without expanding your audience or optimising towards a conversion point higher up the funnel – this reduces your relevance to the audience and your audience’s relevance to you respectively.

Broad audiences are touted as the best practise in Facebook targeting – you allow the algorithm to choose the most likely to convert people from the biggest pool possible. You won’t understand anything about your converting audience and are completely giving up optimisation control to the algorithm. If you have a small budget you will really struggle to make this succeed.

You’ll notice on the above graph that after the point of diminishing returns (PODR) comes the point of negative returns. At this stage, your input:output (or budget:conversions) ratio is so out of whack that you’re spending more on gaining new customers than you’re earning.

For example:

Your online store retails watches at £100. This retail price is designed to provide a 50% ROI, providing £50 profit. When your campaign CPA is at its lowest, your campaign is at the POMY within the current campaign parameters* – let’s say you have a Display campaign CPA of £15. You decide to increase your display investment and subsequently, your CPA increases to £30. At this stage we have hit the PODR, as our increased investment isn’t causing increased conversions. If we were to continue with this strategy and our CPA increased to over £50, we would firmly be in the point of negative returns (PONR); we’ve eaten up our margin in our marketing spend and without enough conversions, we’re spending more money than we’re making.

*Changes such as a pivot in audience strategy, advertising inventory or placements would be considered additional variables to budget. When significant changes are made to the scale of a campaign your POMY will fluctuate based on whether the new assets are more or less efficient.

In summary: without additional changes to strategy, sustained increased investment in a certain tactic will at some point become inefficient. Budget can be re-allocated to mitigate the impact, however longer term it’s important that we optimise each campaign individually as well as managing performance through budget allocation.

So what now?

By the end of Q1 you should have a good idea of where diminishing returns are being hit, whether at a channel level, or more granularly across the campaigns themselves. This means that over the next month, you can:

- Adjust projections for stakeholders,

- Identify any un-allocated budget that can be invested elsewhere to meet our objective

- Note any campaigns which will require more detailed optimisation to increase returns

Join us in April when we’ll be sharing some of the most effective ways to improve in-channel efficiency to make sure you’re getting as much for your budget as possible.

Niki Grant is Head of Search at The Kite Factory. Check out her previous instalments of Performance Planning, a guide for marketers and media planners to handle performance media planning and budget optimisation and her other columns for The Media Leader via Mediatel.