By Digital Business Director Simi Gill

Privacy compliance has rightfully been a key focus for the social platform giants, but are they forgetting about, or deprioritising other legal obligations such as tackling hate speech?

Over the past couple of years, at the top of every online marketer’s priority list has been the adaptation to the evolving legislation, which is changing how we can reach, target and measure users online as we head towards the looming cookieless future. Online privacy has been a hot topic in the United Kingdom since the enforcement of GDPR back in 2018; however, as marketers, we felt this really ramp up in early 2021 when we saw Google release its first version of Privacy Sandbox in gear up to the original cookie phase-out date of Q2 2022. Whilst this didn’t go ahead (due to the Competition & Markets Authority and Information Commissioner’s Office decisions to not yet pass this as a viable alternative solution from Google), there has still been a huge effort from all the major platforms to adapt their technologies, prepare, and reassure marketers that advertising with them will remain efficient and compliant.

For instance, we have seen social giants such as Meta and TikTok improve their ads libraries to increase the transparency of ads ran and the targeting parameters used by advertisers, the declaration of ‘special category ads’, increased prompts for users to review their own personal data settings, further removal of sensitive targeting categories and the evolvement of server-to-server / enhanced tracking solutions. X, in addition to offering increased user privacy controls, has also focused heavily on reinstalling trust with advertisers following extensive brand safety concerns, with further safety partner integrations, ad adjacency controls, new campaign sensitivity settings and the integration of community controls to correct misinformation that can be spread on the platform.

Whilst these developments are essential for a privacy-first, safe internet and are a must-see for online marketers, I remain concerned that other online safety issues that do not fall into GDPR legislation or brand safety specifically are being put on the back foot. Three years ago, I spoke about how Social media giants need to do better to tackle online hate following the outburst of racism seen across their platforms from the Euro 20 final. Whilst I acknowledged that policies regarding hateful content exist on these platforms (see Meta’s here, X’s here, TikTok’s here, YouTube’s here), I concluded that the platforms needed to do better to prevent these comments or pieces of content being allowed to be published in the first place, and that they needed to take further accountability for allowing racism to thrive in their communities.

So, have we seen any significant developments to address this further, at the rate at which we’ve seen the data-privacy developments these past two years?

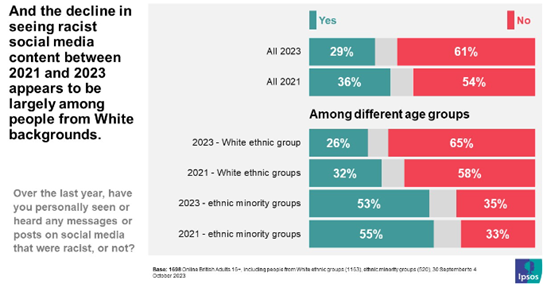

As Ipsos reported at the end of last year, there had been a decline in the proportion of people in Britain from white ethnic groups who reported seeing racist social media content (from 32% to 26% between 2021 and 2023). However, there had been no significant decline in the proportion of people from ethnic minority backgrounds who had seen such racist content (a change of 55% to just 53%). This in itself is clear to show the issue remains a significant threat to the safety of people from ethnic minority backgrounds within these online social communities.

Further to this, Ipsos reported there is still strong support among Britons for action to address racist content on social media, which includes:

- Social media companies removing racist content themselves (77%): Through a combined humanistic and AI approach, all platform policies outline how content is reviewed and removed swiftly if flagged by the systems themselves or reported by other users to be hateful. The Tackling Online Abuse report from The Petitions Committee in 2022 outlines how the social companies they included in their inquiry showcased that a key change from them was through this development of technology, which now allows them to detect and remove content proactively rather than relying on user reports and manual reviews; therefore increasing the volume of removed content quite significantly.

- Social media companies adding warnings to content that might be considered racist (66%): The Meta and X policies note how a pop-up will appear if the platforms deem the draft content inappropriate before posting, prompting the user to review it. I couldn’t find anything in the TikTok or YouTube policies stating a pre-post prompt, but they do outline how their systems will make this assessment when content is ‘under review’ before going live. All platforms also state how they will place proactive restrictions on accounts seen to offend, either through warning / strike-based systems or immediate / permanent suspension (X states it could even be upon a first violation), which is reassuring to see.

- Financial penalties for social media companies who fail to do this (68%): As of 2023, Ofcom is now the formal regulator for online safety, responsible for making online services safer for its users (including services that host user-generated content such as social media). This is a monumental change, as previous arguments from social media companies have came from the angle of not being responsible as they do not generate the content themselves; they are simply a mechanism to host it. The Home Affairs Select Committee previously proposed this should be the case back in 2017 in their report Hate Crime: abuse, hate and extremism online, rightfully claiming “the major social media companies are big enough, rich enough and clever enough to sort this problem out – as they have proved they can do about advertising or copyright. It is shameful that they have failed to use the same ingenuity to protect public safety and abide by the law as they have to protect their income.” Therefore, it is hugely positive to see Ofcom now state that “under these new rules, we will have powers to take enforcement action, including issuing fines to services if they fail to comply with their duties.” The law now “places a legal responsibility on social media platforms to enforce the promises they make to users when they sign up”. This could result in a fine of up to £18M or 10% of their global revenue (whichever is biggest). Therefore, the scale of this monetary threat is enormous and could even reach billions of pounds.

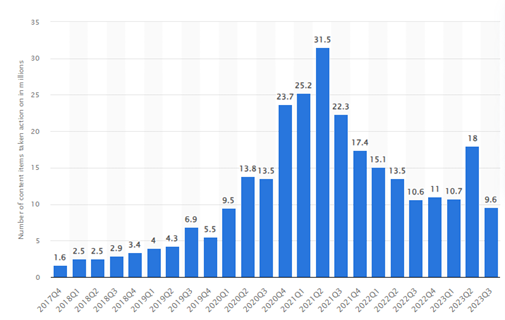

When looking at the number of hateful comments removed from Facebook (worldwide) from Statista after a surge in 2021 (following the pandemic), the rates have been on a downward trend – except one spike in Q2 2023 at a staggering 18 million pieces of hate speech. In Q3 2023 Facebook removed 9.6 million pieces of hate speech, which is 47% down from the previous quarter.

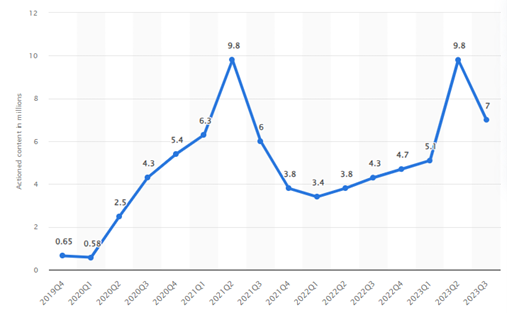

Statista showed that Instagram followed a similar trend, but it was considerably less than the volume found on Facebook, with 9.8M pieces of hate speech at the peak of Q2 2023 and 7M in Q3 2023.

For YouTube, Statista reports that of those videos removed in Q3 2023, hateful or abusive content accounted for 2.3%, the lowest it has been since Q4 2021 and the fourth lowest category overall of all reasons a video can be removed.

Hate speech on social media is an ongoing challenge, and opinions may always be divided. It is alarming that according to a Statista May 2023 survey of worldwide internet users, approximately 37% of respondents believe that social media platforms should allow harmful content, 33% said the opposite, while nearly 30% were unsure. Those 37% of people may always argue that social media exists to allow for freedom of speech and ‘personal expression’. Further to this, there is a challenge in that “there is no universally acceptable answer for when something crosses the line…language also continues to evolve, and a word that was not a slur yesterday may become one today” (Richard Allan, VP EMEA Public Policy at Meta wrote back in 2017); so vs the likes of factual Personally Identifiable Information which forms the legislation of GDPR, it can make it difficult to police in a similar way.

From reviewing current platform policies, there have been improvements in how hateful content is managed overall, specifically as AI technology is developed further and used alongside manual reviews to remove easily identifiable hateful content swiftly or, even better, automatically. However, in the same way that we as digital advertisers utilise contextual targeting online, we must ensure the contextual partners have the correct AI and technology in place to recognise semantics – it is not enough now to simply target off a keyword alone. We need to ensure that technologies are keeping up with scanning and understanding the context of the whole page or content we are targeting to be sure we have complete brand safety, so the same goes for social media content. There is still a way to go for social media platforms to develop their AI to adapt to ever-evolving language, pick up slurs, assess broader phrases that may not include triggering keywords, and even recognise the harmful use of emojis. It’s also important to note how regularly the hateful content policies are reviewed and updated – i.e., TikTok and X appear to have updated theirs as recently as April 2024. Still, it seems Meta hasn’t updated since 2021, and YouTube even more worryingly since 2019.

One of the most significant developments is Ofcom’s power to take enforcement action, and the development of law in the United Kingdom regarding social media companies’ responsibility to uphold a safe environment for its users and be held accountable. This is a crucial step, and it’s unfortunate that such enforcement has taken so long to be implemented. We also need to place more expectations on social media companies to report and pass on individuals’ information to the police when such crimes have occurred. This ensures the action goes beyond their own punishments (such as permanent account suspension), and this real-life coincidence should be clearly communicated to these users when their posts are flagged, taken down or blocked to ensure they understand the severity of their actions.

Ultimately, the facts are the facts – racism and hate speech are a crime – if it is illegal offline, it is illegal online. The United Kingdom imposes various criminal prohibitions on hate speech, both online and in print. The Crime and Disorder Act, Public Order Act, Malicious Communications Act 1998 and Communications Act 2003 all prohibit speech that is derogatory on grounds of race, ethnic origin and religious and sexual orientation. These acts, alongside the most updated Online Safety Bill 2023, must therefore be taken as seriously as GDPR law by social media platforms, where this hate can be fostered and spread so quickly. We will need to continue to apply pressure on the social giants to uphold this, just as we are to ensure they are operating compliant, data safe and privacy-first platforms.

We are all looking forward to Euro 2024 kicking off, and I hope that social platforms will be used solely to celebrate this, not attacking players and allowing racism to occur as we saw in 2021. There may always be hateful content that slips through the cracks and goes undetected by social platforms (as we know, comments and content can gain traction or go viral in the blink of an eye online), but should this happen, I hope to see a far swifter rate of action, severe punishments on individual users committing these crimes and fines issued to the platforms when their commitments to safety, and their legal obligations have not been upheld.

They can, and must, continue to do better.

Sources;

- https://transparency.meta.com/en-gb/policies/community-standards/hate-speech/?source=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fcommunitystandards%2Fhate_speech

- https://help.x.com/en/rules-and-policies/x-rules

- https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2801939?hl=en&ref_topic=9282436

- https://www.ipsos.com/en-uk/racism-and-social-media

- https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5802/cmselect/cmpetitions/766/report.html#heading-2

- https://www.ofcom.org.uk/news-centre/2023/online-safety-ofcom-role-and-what-it-means-for-you

- https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmhaff/609/60902.htm

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/1013804/facebook-hate-speech-content-deletion-quarter/

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/1275933/global-actioned-hate-speech-content-instagram/

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/1132956/share-removed-youtube-videos-worldwide-by-reason/

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/1403405/social-media-harmful-content-allowing-worldwide/

- https://about.fb.com/news/2017/06/hard-questions-hate-speech/

- https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/uk-gdpr-guidance-and-resources/personal-information-what-is-it/what-is-personal-information-a-guide/#1

- https://researchoutreach.org/articles/hate-speech-regulation-social-media-intractable-contemporary-challenge/

- https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/uk-gdpr-guidance-and-resources/personal-information-what-is-it/what-is-personal-information-a-guide/#1

- https://www.gov.uk/government/news/britain-makes-internet-safer-as-online-safety-bill-finished-and-ready-to-become-law#:~:text=If%20social%20media%20platforms%20do,could%20reach%20billions%20of%20pounds.